Holding

Entries - Direct, Parallel, Teardrop

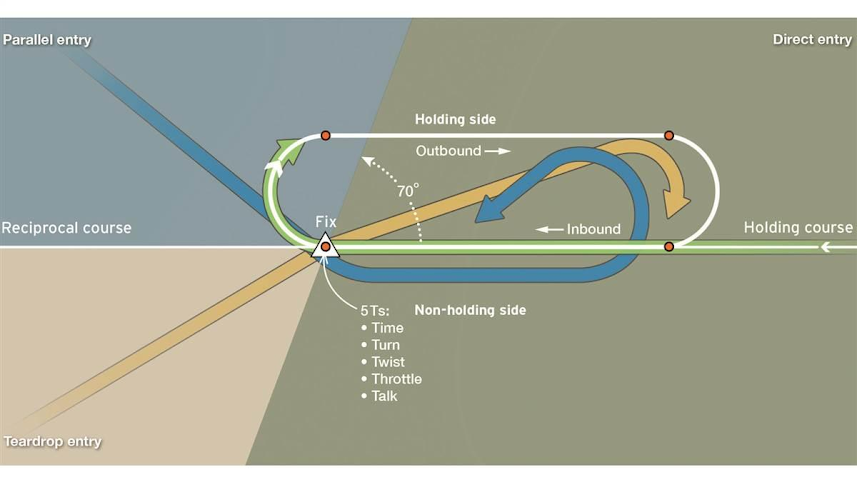

A holding instruction will usually include:

In GA flight, I have never received a non-published hold from ATC. Although, I have requested and received clearance plenty of non-published holds during training as well as my checkride. Research AIM 5-3-8 for further details. After selecting the procedure to enter a holding pattern, there’s a sequence to follow after crossing the holding fix. The “5 Ts” don’t have to follow any strict order, but the first step really should be to start timing, because you’ll be flying for a one-minute interval as you enter the hold. “Turn” stands for making the turn to the first entry heading—either a 180-degree turn (for the direct entry), a procedure turn to intercept the inbound holding course (teardrop entry), or a turn to parallel the holding course outbound (parallel entry). “Twist” stands for resetting the inbound holding course on your VOR or GPS receiver; “throttle” means set power to fly at a comfortable, and proper, holding speed. “Talk” refers to the radio call advising ATC that you’ve entered holding (and when leaving an assigned holding fix, another call should be made). At the points marked in red, timing is also initiated so that you can be sure of making one-minute turns or legs, and holding course guidance should be on your nav display(s) so that you can judge your course interception inbound to the holding fix. Must the interception procedure be flown exactly as depicted? Do your best, but stay on the holding side If you’ve held the idea of holding as an intellectual exercise, performed only during practice flights, stress levels can rise as you quickly write down the clearance, figure out the VOR’s location, and think about the correct holding pattern entry procedure. Maybe we should practice holding patterns more often. That’s because holding clearances can be issued for many reasons. Most often, it’s to create adequate spacing between IFR traffic in busy airspace, and not just in the en route phase of flight. Holding also can be used as you near your destination. Airplanes may even be cleared to hold at the same fix, but stacked at different altitudes. This is most likely to occur where low instrument meteorological conditions—ceilings below 500 feet, visibilities below one mile—mean strict ATC spacing and sequencing rules. As the airplane holding at the lowest altitude in the stack is cleared for the approach, those above it are cleared to descend and hold at progressively lower altitudes, until it’s their time to shoot an approach. Some call this “shaking the box.” When the weather is above low IFR limits—ceilings 500 to 1,000 feet, visibilities between one and three miles—holding at feeder, initial, and even final approach fixes may also be used. Just be aware that there may be VFR traffic in or near the airport. The airport’s traffic pattern altitude could be below the ceiling, and experiencing visual meteorological conditions. Airplanes could legally be flying traffic patterns even though IFR arrivals are happening at the same time. To help prevent any nasty surprises as you descend on your straight-in IFR final approach course, it’s best to look for any ADS-B targets and listen to CTAF frequencies for the locations of any self-announcing traffic. Remember, ATC’s primary job is to separate aircraft on IFR flight plans, not work VFR traffic around instrument arrivals or departures. Holding can be used as a substitute for a procedure turn outside an instrument approach’s final approach fix. This is called a hold in lieu of procedure turn, abbreviated HILPT. A quick look at the approach plate’s holding pattern symbology will tell you if you need to fly a HILPT. If the holding pattern’s racetrack is in bold, you must fly the holding pattern to reverse course—unless ATC clears you for a straight-in final, the “No PT” (no procedure turn) advisory is depicted, or ATC is providing radar vectors to the final approach course.  Winds can complicate your tracking. Crab to compensate for crosswinds (above) or else a one minute turn from the outbound path could leave you undershooting or overshooting your intercept to the holding course. Finding the optimal crab angle may take a few turns around the pattern once established on the inbound leg, which should be one minute in duration. To prevent being blown too close—or far away—from the inbound leg, it might make sense to double (or even triple) the wind correction angle you used to track the inbound leg’s course. Headwind on the inbound course? Shorten your time on the outbound leg. Tailwind on the inbound course? Extend your time flying on the outbound leg so that you reach the magic, one-minute (or one and a half minutes, if flying above 14,000 feet) inbound leg timing. A holding pattern is part of a missed approach procedure. When you practice missed approaches, do they always end with a missed approach hold? They should. You’ll wish you practiced them more often because in real-world IMC, flying a full-blown miss is a high-workload job. Once you’ve decided to fly the miss, you’ll need to power up, enter a climb, announce your missed approach to ATC, retract gear and flaps, retrim, fly to the missed approach point, enter the holding pattern, report your time and altitude to ATC, reduce power, retrim, and track the pattern’s inbound leg. Good thing that many missed approaches begin with straight-ahead climbs to holding fixes that are dead ahead. Want more situations where a hold might be necessary? An airplane ahead of you has a gear-up landing, closing the airport. At a nontowered airport, a pilot forgets to call ATC to close the flight plan. The ILS or VOR serving the approach goes out. The weather goes below minimums. In each case you may well need to hold and then fly elsewhere. Think some more, and you can envision other reasons. You may even face situations where you’d ask ATC for a hold. Let’s say you need time to troubleshoot a system problem, study an upcoming procedure, or check on weather at alternate airports. The expect further clearance (EFC) term in a holding clearance is important because it makes the holding fix your clearance limit. You should make sure you’re issued an EFC in case you lose communications with ATC. If you lose communications when you’re holding at an en route or other fix that isn’t associated with an instrument approach, leave the holding fix at the EFC and fly to a fix from which your approach begins. Then start your descent and approach as close as possible to your most recently calculated estimated time of arrival (ETA), based on any clearance amendments. If your clearance wasn’t amended, use the ETA you named in your flight plan. If you lose communications and your holding fix is a fix where an approach begins—an initial, intermediate, or final approach fix—then begin the descent, or descent and approach—as close to the EFC as you can. No EFC? Then as close to the ETA as possible. For the full lowdown on lost communications, check FAR 91.185. Along with an EFC, ATC should also keep you advised of any expected delays, and give the time of the delay duration. The worst case would be the dreaded “delay indefinite” message, followed by another EFC time—which means additional turns around the holding pattern. With the popularity of full-featured GPS navigators and their big-screen moving maps, it’s easier to do the mental gymnastics needed to orient yourself to the holding fix and the legs of the pattern. They even tell you the correct holding pattern entry! But full familiarity is vital when it comes to flying holding patterns. Recent Garmin navigators, for example, require that you use the OBS function to define the inbound leg of the holding pattern and suspend sequencing. If you don’t, you’ll navigate to the next fix in the flight plan instead of staying in the holding pattern. However, guidance to and around missed approach holding patterns can be automatic. And if on autopilot, the airplane will continue to hold until you select another operation. That’s a far cry from the bad old analog, round-gauges-only days. The basics may remain the same, but those of us flying with flight directors, autopilots, and automated navigation definitely have a big advantage. DEFINITIONHolding means flying an approximate race-track pattern to and away from a holding fix which may be a VOR, NDB, intersection or DME fix.SAFETY FACTORSKnowledge and skill in holding develop the pilot's proficiency in planning, orientation, and division of attention thus enhancing flight safety.Holding may be a means to delay arrival until airport conditions are improved and approach and landing may be more safely accomplished. TOLERANCESInstrument Rating PTS (FAA-S-8081-4D)III.C. Holding procedures To determine that the applicant:

OBJECTIVESEncourage mastery of holding patternsDevelop student knowledge and skill in holding patterns to satisfy the Instrument Pilot PTS PROCEDURESPreflightDiscuss 5t's Turn, Time, Twist, Throttle, Talk

COMMON ERRORS

Holding PatternLooks like a racetrack, typically found at a miss approach. It designed to keep the aircraft relatively stationary over a navigation fix (usually a VOR, NDB, or a DME point on a VOR radial). Holds are fundamental to IFR training and provide an excellent means of developing instrument flying skills.Standard Holding PatternThe position of the hold is assigned by ATC or is in accordance with a published chart or plate. The goal is to enter the hold smoothly after crossing the fix, and then produce a series of racetrack patterns in which a one-minute leg is flown inbound along an assigned VOR radial or NDB track. The quicker you are at establishing a precise one-minute inbound track, the more highly regarded are your instrument skills. In calm winds, the manoeuvre is relatively straight forward (once you get the entry sorted out), but the trick is producing an accurate hold in windy or turbulent conditions. Unless otherwise advised, all turns in a hold are to the right. The depiction below is the Standard Holding Pattern and its component parts. An aircraft flying the above hold would be described as “holding inbound on the 270° track,” in the case of an NDB hold, or “inbound on the 090° Radial,” in the case of a VOR. The hold is “standard”—meaning that turns are to the rightHold ConsiderationsRemember that the name of the game is to nail the hold as quickly as possible—this includes both tracking and timing. Some things to remember:The wind correction required on the inbound track should be doubled during the outbound track; in slower aircraft this correction sometimes appears unbelievable—nevertheless, trust the formula. The point at starting the timing on the outbound leg must be the same every time—any error here will throw your timing out. Starting the timing for the inbound leg should be initiated when the inbound track is intercepted, or when the wings are levelled (in the event an intercept is required). During the inbound turn, study the movements of the needles carefully. In the case of a VOR hold, note when the track bar begins to show signs of migrating. If you are behind in your turn, smoothly increase your bank to the maximum acceptable for instrument flying—30° of bank (be careful doing this as you increase the complexity of the turn (by adding the need for delicate pitch-up inputs, and you increase the risk of vertigo). In the case of an NDB hold, remember that a properly flown hold in calm winds should produce a 30° deflection off your tail just before you initiate your inbound turn. As the inbound turn is made, watch the position of the ADF needle in reference to the inbound track on your heading indicator—your ability to visualize the ADF needle on the heading indicator in reference to the inbound track will help you modify your bank Holds

Hold ClearancesHold clearances follow a prescribed format, including usually the routing to the hold fix, the side of the fix you are to hold on (e.g. west, south-west, etc.), the exact VOR radial, NDB track, or Airway, the altitude you are to maintain, and the time at which you can expect a further clearance (just in case your radio quits you won’t be caught in the hold). Here is an example: Controller: “ABC, I have your hold clearance when you are ready to copy.” Pilot: “Go ahead with the hold clearance for ABC.”1 Controller: “ABC, you are cleared direct to the Whatcom VOR. Maintain 4000’. Hold southwest of the 230° Radial. Expect further clearance at 2150.” Pilot: “ABC is cleared direct to the Whatcom VOR. Maintain 4000’. Hold southwest on the 230° Radial. Expect Further at 2150.” Controller: “ABC, readback correct.” The hold manoeuvre is of course an IFR manoeuvre, and IFR pilots are legally required to readback a clearance. Just to minimize errors, clearances are normally written down. Hold EntriesThe prospect of flying a hold is really straightforward. You simply fly inbound on the assigned track on which the hold is defined, and, after the fix is crossed, turn outbound and fly the reciprocal heading. In calm winds, the procedure is relatively easy (in wind conditions, the process is a little more complicated, and this is discussed below). Where students do find holds challenging is with respect to the entry procedure. So, while flying a hold is generally easy once established, it is the hold entry where you will be tested.To understand the hold-entry procedures, you must first understand that the aircraft can approach the fix (direct track) from any direction, so the challenge rests with trying to figure out the initial turns that must be accomplished to end up tracking inbound on the assigned holding track (the inbound track). Essentially, there are three hold-entry patterns, which are derived from three sectors of origin as described above.2 The hold-entry patterns, incidentally, are mandatory and must be flown as prescribed in the AIM (RAC 10.5) and the Instrument Procedures Manual.3 Based on the sector from which you approach the assigned fix, the three entry procedures are defined as the parallel entry, offset entry, and direct entry. A simple technique for determining the hold-entry pattern to be flown (based on the sector of origin) will be described below, but first, let us examine the three entry patterns Direct EntryDirect entries are just plain easy. Proceed directly to the assigned fix, and then, after crossing the fix, simply turn right (standard hold) to the outbound heading. After passing “abeam” the fix outbound on the outbound heading, start your timer and fly for one minute. Then, initiate a right turn to intercept the inbound track. In calm winds you will produce a one-minute track on the inbound leg. A depiction of the direct entry is provided below Offset EntryAfter crossing the fix during an offset entry, turn to a heading that is 30° less than the outbound heading; fly this “offset” heading for one minute than turn right and intercept the inbound track. Here is the pattern for the offset entry Parallel EntryAfter crossing the fix during a parallel entry, simply turn to the outbound heading of the hold—maintain that heading for one minute, then turn in a direction opposite to the hold turns—that is, turn to the left (“parallel is opposite”). After the turn is flown for one minute, roll out so as to track directly to the fix and essentially fly a direct entry (turn right to the outbound heading after crossing the fix) The POD Method of Hold EntryThe decision-making of a pilot can be taxed a great deal, especially during the holding procedures flown in conjunction with an IFR approach procedure. It is during this time that the IFR pilot must assess the weather governing his approach, the instructions provided by ATC, and the approach procedures to be used. With all this to consider, it makes sense that a holding assignment should not present any more decision-making effort than required—carrying out that assignment should be as simple as possible. Flying a holding pattern is not difficult. Wind correction and timing adjustments are crucial, but there is lots of time (four minutes or longer per circuit), and it is expected that the pilot exercise “trial and error.” The tricky part is the entry. More specifically, the IFR pilot can be faced with having to record, read back a hold assignment, plus decide on the entry headings to be flown, within minutes of reaching a fix. These few minutes just prior to entering a hold are crucial and an IFR pilot must be trained to accomplish the tasks safely as quickly as possible. This is where the POD Method fits in. The POD Method essentially “frees up” your decision-making. When a hold clearance is received, the first reaction is an attempt to “visualize” how the hold looks on the map. Using a mental map, we attempt to place our aircraft relative to the assigned fix, and then draw how the hold will look—“If I approach from this track, I will cross the fix and steer a heading of . . .” Too slow! Instead, using the POD Method, we use the heading indicator as an “entry aid.” As we approach the fix, the heading to the fix appears at the top of the heading indicator (assuming, that is, you are proceeding directly to the fix, which will always be the case with a hold clearance). We then visualize an inverted “T” centred on the instrument as indicated below ote that the thumb rotates the lateral line 20° as indicated. Once the imaginary sectors are mapped on the heading indicator, the rest is easy. Simply visualize which sector the outbound track of the assigned hold lies. If the outbound track is in the “P” sector, the pilot performs a parallel entry procedure; if the outbound track is in the “O” sector, an offset entry procedure is flown; finally, if the outbound track is in the “D” sector, the pilot flies a direct entry procedure. Simple, don’t you think? Practise the POD method with a piece of paper. The more times you practise it, the better you will be in the cockpit: Draw a circle and assign yourself a random heading to a fix. Map out the POD, including the 20° “slide”; each sector border should have a heading. Write out an imaginary hold clearance with random headings. Determine your outbound track, place it on the map, and determine the entry procedure. Confirm your choice by drawing your fix and hold and the path of the aircraft. Remember, the idea is to determine the hold entry as quickly and as accurately as possible. When practising in the air, incorporate the POD method as standard procedure: ATC hold clearance. Write and readback. Tune, Identify, Select and Test the navigation aid (if applicable). Turn direct to fix and/or determine heading direct to fix. Map out the POD and place the outbound track to determine entry procedure. Crossing fix:

ATC Holding Clearance /Holding Pattern Achieve the skill and knowledge required to enter and remain within a published or non-published holding pattern Holding pattern are usually found at busy airports where ATC can put aircraft in holding patterns to sequence aircraft for landing, and it can be found at Miss Approach

Holding pattern has a Right hand turn Fix is a stationary waypoint Fix can be a VOR, DME , GPS Waypoint, Intersection, NDB Holding Pattern is a Race track pattern and it has 4 components 1. Inbound leg to FIX 2. Fix End (semi circle) 3. Outbound leg 4 Outbound End (semi Circle) ATC Holding Clearance (template) 1. Name of the FIX 2. Direction of the inbound leg from the FIX 3. Radials/Berings that define the inbound leg 4. Turn Direction (if non-standard) 5. Leg length (if non-standard) 6. expect further Clearance Time (EFC) 7. Any Applicable notes Example of Holding Pattern from ATC "Sioux 44, proceed direct to the GFK VOR, hold south east on the 150deg radial left hand turn, 5 mile legs, expect further clearance 1355Z" Applied ATC Holding Clearance 1. FIX - GFK VOR 2. Direction of inbound leg from fix - hold south east 3. Radial defined inbound leg - 150deg radial 4. Turn Direction - left hand turn 5. Inbound leg - 5 mile legs 6. expect further clearance 1355Z There are 3 ways to enter the fix 1. Direct 2. Parallel 3. Tear Drop Direct Entry - Pilot Crossing the FIX and immediately turning to the outbound leg Parallel Entry - Pilot Crossing the Fix and turn parallel the inbound leg on the non inbound side , fly outbound for 1 minute then turning towards the inbound side of the FIX and establish an intercept for the inbound leg. Tear Drop Pilot Crossing the FIX and flying approx 30deg angle to the inbound leg on the holding side of the fix for 1 minute then turning to intercept the inbound leg 5 T's of a Holding Pattern Turn - for the Tear drop entry Time - Beginning timing for 1 minute as the aircraft crosses the VOR Twist - Twisting the OBS setting to 360deg/TO flag for correct sensing on inbound leg Throttle - Adjust Throttle for proper holding speed Talk - To let ATC know that Aircraft Sioux 55 is established and holding at 6,000 feet, time 1340 Zulu Timing on the outbound leg will alway start when the pilot abeams the FIX This is where the TO/FROM indication flips in the cockpit This is the time when outbound TIMING can start Section 6. Holding AircraftCLEARANCE TO HOLDING FIXConsider operational factors such as length of delay, holding airspace limitations, navigational aids, altitude, meteorological conditions when necessary to clear an aircraft to a fix other than the destination airport. Issue the following:

PHRASEOLOGY- EXPECT FURTHER CLEARANCE VIA (routing). EXAMPLE- “Expect further clearance via direct Stillwater V-O-R, Victor Two Twenty‐Six Snapy intersection, direct Newark.”

NOTE- The most generally used holding patterns are depicted on U.S. Government or commercially produced low/high altitude en route, area, and STAR Charts. PHRASEOLOGY- CLEARED TO (fix), HOLD (direction), AS PUBLISHED,

NOTE- Additional delay information is not used to determine pilot action in the event of two‐way communications failure. Pilots are expected to predicate their actions solely on the provisions of 14 CFR Section 91.185. PHRASEOLOGY- EXPECT FURTHER CLEARANCE (time), EXAMPLE-

PHRASEOLOGY- EXPECT FURTHER CLEARANCE (time),

NOTE-

PHRASEOLOGY- DELAY INDEFINITE, (reason if known), EXPECT FURTHER CLEARANCE (time). (After determining the reason for the delay, advise the pilot as soon as possible.) EXAMPLE- “Cleared to Drewe, hold west, as published, expect further clearance via direct Sidney V-O-R one three one five, anticipate additional two zero minute delay at Woody.”

PHRASEOLOGY- VIA LAST ROUTING CLEARED.

NOTE- Except in the event of a two‐way communications failure, when a clearance beyond a fix has not been received, pilots are expected to hold as depicted on U.S. Government or commercially produced (meeting FAA requirements) low/high altitude en route and area or STAR charts. If no holding pattern is charted and holding instructions have not been issued, pilots should ask ATC for holding instructions prior to reaching the fix. If a pilot is unable to obtain holding instructions prior to reaching the fix, the pilot is expected to hold in a standard pattern on the course on which the aircraft approached the fix and request further clearance as soon as possible.

REFERENCE- FAA Order JO 7110.65, Para 5-14-9, ERAM Computer Entry of Hold Information

PHRASEOLOGY- (Airport) ARRIVAL DELAYS (time in minutes/hours). When issuing holding instructions, specify:

NOTE- The holding fix may be omitted if included at the beginning of the transmission as the clearance limit.

PHRASEOLOGY- HOLD (direction) OF (fix/waypoint) ON (specified radial, course, bearing, track, airway, azimuth(s), or route.)

EXAMPLE- Due to turbulence, a turboprop requests to exceed the recommended maximum holding airspeed. ATCS may clear the aircraft into a pattern that protects for the airspeed request, and must advise the pilot of the maximum holding airspeed for the holding pattern airspace area. PHRASEOLOGY- “MAXIMUM HOLDING AIRSPEED IS TWO ONE ZERO KNOTS.” You may use as a holding fix a location which the pilot can determine by visual reference to the surface if he/she is familiar with it. PHRASEOLOGY- HOLD AT (location) UNTIL (time or other condition.) REFERENCE- FAA Order JO 7110.65, Para 7-1-4, Visual Holding of VFR Aircraft.

Approve a pilot's request to deviate from the prescribed holding flight path if obstacles and traffic conditions permit.

Separate an aircraft holding at an unmonitored NAVAID from any other aircraft occupying the course which the holding aircraft will follow if it does not receive signals from the NAVAID.

When the official weather observation indicates a ceiling of less than 800 feet or visibility of 2 miles, do not authorize aircraft to hold below 5,000 feet AGL inbound toward the airport on or within 1 statute mile of the localizer between the ILS OM or the fix used in lieu of the OM and the airport. USAF. The holding restriction applies only when an arriving aircraft is between the ILS OM or the fix used in lieu of the OM and the runway. REFERENCE- FAA Order 8260.3, United States Standard for Terminal Instrument Procedures (TERPS), Chapter 17, Basic Holding Criteria. Atlanta CENTER - Deals with Departure - Flight to Cruze - Broken up into Sectors and monotor by Airtraffic Controlls - Transfer occurs about 3 mins from boundry (as “flashing” at the next sector) - Once the receiving the controller accepts the handoff (step 1) communications are transferred - Contact XXX on XXX.XX - Contact APPROACH Atlanta TRACON (Terminal Radar Approach Control) - Handles Approachs and Departures - Responsible to all traffic in and out of airport - from Surface up to 14,000' - All traffic about 40 miles of atlanta - First people Pilot talks to when they are in the air - Last people they talk to before landing - get aircraft to Final Approach then switch to Tower (7-10 miles) Atlanta TOWER - Clear to land - Clear to Take off - Contact Departure on a certain frequency - "Departure" is at the TRACON who will then send them to CENTER. Atlanta GROUND http://expertaviator.com/2016/07/15/understanding-atc-handoffs/ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=waAdGCVa_Bo https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YbIw6kdytnU&spfreload=5 Reference: http://www.langleyflyingschool.com/Pages/Holds%20and%20Hold%20Entriesl.html |

No comments:

Post a Comment